Techs can’t solve the problem that can’t be found

We take many modern automotive conveniences for granted, and windshield wipers must be somewhere near the top of the list. You don’t think about them much until you’re driving in the rain with worn blades or, far worse, a bad wiper motor or linkage. Even on a clear day, not being able to clean a grime-covered windshield is infuriating. Suddenly this basic feature feels absolutely critical.

But wipers weren’t an obvious feature on the first automobiles, and it took decades for manufacturers to land on a standard design. In the meantime, lots of inventors proposed and patented different solutions, often around the same time, leading to lots of overlapping innovation, and subsequent disputes over who deserved the credit. And after all that, we’re still tinkering on new designs today.

None of this could’ve been predicted in the first years of the 20th century, when even cutting-edge cars were glorified beach buggies. They were either entirely topless, or almost literally looked like horseless carriages, a.k.a. fancy rectangles with headlights. The fastest vehicles at the time couldn’t even reach the maximum speed limit in most U.S. states today, while the average top speed was only 20 mph. When people had rain on their windscreen, they just took off the windscreen.

Nevertheless, a few different people all simultaneously documented systems that would allow someone to manually move a mechanical arm from the inside of the vehicle that would wipe rain, snow, and anything else off a window. Seemingly the first American to patent one for an automobile – as opposed to a locomotive – was Mary Anderson, who in 1903 created “a device operating on the outside of the glass to remove snow, rain, or sleet from the center-vestibule-window of modern electric-motor cars.” She said she was inspired by traveling in New York City during a snowstorm.

“The motorman had to keep the windshield down so he could see out,” read Anderson’s obituary in the Birmingham Post-Herald. “Miss Anderson noted there was no reason to keep the window down and let the foul weather in. She came back to Birmingham and invented the original fan-type windshield wiper – which was turned by hand.”

Image from Mary Anderson’s patent. Source: Google Patents.

Anderson tried to sell her idea, but found no takers, and her invention never made it into production. One firm she tried to enlist in selling the idea wrote her a letter saying “we regret to state that we do not consider it to be of such a commercial value as would warrant our undertaking its sale.” Anderson’s great-great-niece speculated to NPR that it was tough trying to market an invention as a woman in those days. There were also only 32,000 registered vehicles in the U.S. at the time.

Not surprisingly, as the number of vehicles on the road increased, so did the number of wiper-related inventions, totaling hundreds of patents issued every decade from the 1920s to today. This seems crazy until you look at some of these patents and realize how many different ways you could do the job without the benefit of hindsight.

Take U.S. Patent 1,227,100 a “Wind-Shield Cleaner” designed by Ormond Wall, issued May 1917. It had a bar running vertically through the center of the windshield, with a wiper arm that pivoted in the center of the bar, powered by an electric motor, presumably making a nice bowtie shape.

Or look at U.S. Patent 1,274,983, a “Cleaning Device” designed by Charlotte Bridgwood, issued August 1918. (A great year for automotive innovation in general.) Her design also had the wiper blades mounted vertically to a track that would carry them from left to right across the whole windshield and back again, cleaning the surface on both the inside and outside. This has been referred to as a roller-style device vs. the fan-style Anderson and Wall patented.

There are many more, but the first to make it as standard equipment on a production automobile was U.S. Patent 1,183,463, another “Wind-Shield Cleaner” designed by John Jepson, issued May 1916. Jepson’s design made use of the fact that some vehicles of the time had two-piece windshields, with a top pane, lower pane, with a small space in between. The top pane could rotate so that you could fit the squeegee device through, close the pane, and then move the blades back and forth using a handle on the inside.

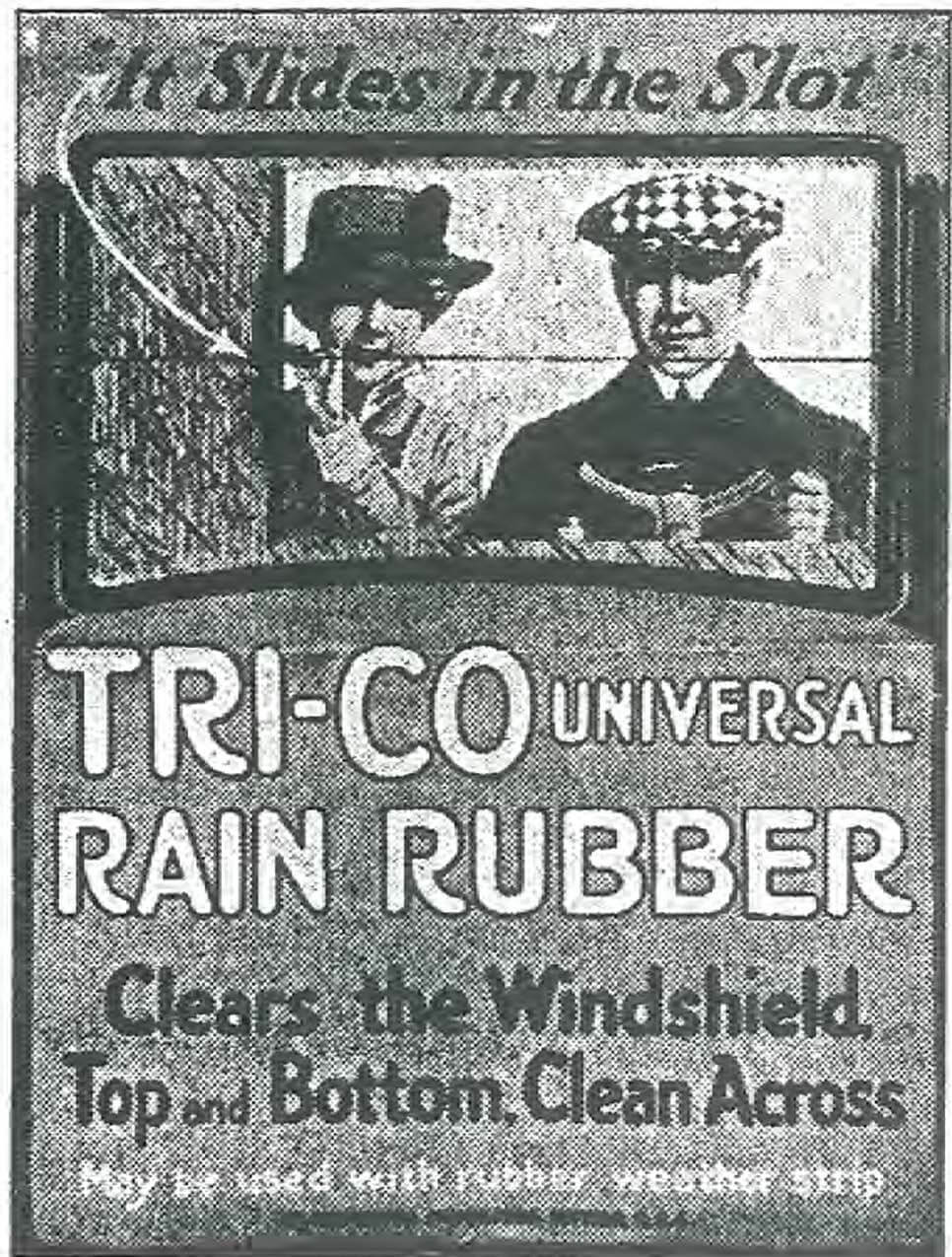

Oishei was a theater manager, but in 1916 he was driving in the rain and hit a bicyclist. The rider wasn’t injured, but Oishei said it was a “harrowing experience that imprinted on my mind the definite need for maintaining vision while driving in the rain.” When he then saw Jepson’s invention around town, he proposed the idea of partnering to market the product, which was renamed Rain Rubber. “It Slides In the Slot” and “Would YOU Drive Blindfolded?” was some of the copy on its early ads and packaging.

Early ad for Rain Rubber. Image source: John R. Oishei Foundation, Buffalo & Erie County Public Library

By 1919, the local Pierce-Arrow Motor Company made Rain Rubber standard on its luxury models, and Packard, Cadillac and Lincoln did the same the next year. After World War I, the company expanded to two more continents, Europe and Australia, so they called themselves Tri-Continental Corporation, then Tri-co, then Trico Product Corporation. Today, Trico claims this made Rain Rubber the first mass-produced, commercially available wiper blade.

As automakers changed their designs, windshield wipers had to change too. The two-piece windshields went away, making Rain Rubber obsolete. They also introduced curved windshields, requiring different blade styles. And, of course, manually cleaning your windshield while driving is dangerous and kind of ridiculous in retrospect.

In U.S. Patent 1,424,890, William Folberth, from Cleveland, proposed a more automatic solution. His system used vacuum from the intake manifold, connected by a hose to power a vane motor, which use a rock shaft to move the blades back and forth. The patent was issued in 1922. It got the job done, albeit with the flaw that the speed of the wipers was tied to the amount of air being sucked into the engine. The lower the pressure, the slower the blades.

Folberth and Trico immediately became competitors, until Trico purchased Folberth’s company for $1 million, or what would be about $16 million today. That might have been a pretty good deal, because in a couple years, 70% of new vehicles had either the vacuum-operated or hand-operated Trico wiper.

From the 1940s to the 1970s, Trico wound up in several other technology disputes, such as with rival Anco. But the most famous case of wiper patent infringement was filed in 1978 by Robert Kearns, who patented an intermittent windshield wiper a decade earlier.

Kearns was immortalized in the 1993 New Yorker article “The Flash of Genius,” which was later developed into a 2008 movie of the same name. A serial inventor, he claimed to have presented Ford engineers with his idea, only for the company to decline licensing his idea, and then implement the same technology. He sued in 1978, and finally won his suit in 1990, with Ford agreeing to pay $10 million. He sued Chrysler as well, and received $30 million in 1995.

It can seem like windshield wipers are a pretty mature technology today, without much variation or opportunity for innovation, but in many ways there are just as many evolving approaches to windscreen clearing as there were a century ago.

While the bottom-mounted, fan-style, parallel wipers are clearly the standard everyone’s used, there are still a variety of different wiper geometries in operation. There are also continuous tweaks to the various pieces of the system, such as different blades styles (e.g. beam-style blades that maximize contact points), washer systems (e.g. AquaBlade and Magic Vision Control), and both heated wipers and windshields (e.g. VisioBlade). Some examples:

Meanwhile, entirely new cleaning systems are still being imagined. In just the past few years, Tesla’s patented an electromagnetic system, as well as one that would use frickin’ lasers. The wiper system is one of the most discussed features on one of the most discussed new vehicles in recent memory – the Tesla Cybertruck. Many people have speculated if it will use one of these futuristic new technologies, and some have even flown drones over Tesla’s facilities to get a glimpse of its development.

Manufacturers have to ship cars with side mirrors by law, but owners are allowed to modify their cars.

The wiper is what troubles me most. No easy solution. Deployable wiper that stows in front trunk would be ideal, but complex.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) December 10, 2021

After 120 years and thousands of patents, it’s almost like we should consider replacing the old cliché of building a better mousetrap with building a better windshield wiper.

This article is from an occasional series called The Best Part that tells the fascinating stories behind car parts. Have any ideas for other parts with cool backstories? Let us know in the comments below.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.