“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

When I got to Dorman, I wasn’t bowled over by our chassis parts for one reason: for the most part, they are sealed. We do have a line of severe-service chassis parts (Premium RD™), but the bulk of our passenger-car offerings feature polymer bearings and the grease within is meant to stay there for life.

And that ran afoul of what I “knew.” Metal-on-metal bearings are always better, right? And a chassis part without a grease zerk fitting on there must have been made that way to save money.

And then someone told me I was wrong. Dave Grasso, a friend and wrench whose opinion I value (and the category manager for our chassis pieces) pointed out some things that caused me to swing my viewpoint around.

Chassis inspection during routine maintenance. Photo: Mike Apice.

Dave pointed out to me that polymer bearings had come a long way since I started turning wrenches, and that’s not wrong. Longevity is better as we all have seen—it’s part of the reason you’ll see so many sealed chassis components in use by the OEMs and also why you see so many of those parts lasting well beyond the warranty periods, which are also longer than they once were.

Steering effort is reduced, too, and feel is better. Sure, metal-on-metal bearings were fine in Ackerman-style front end setups. Steering slop was expected. But modern electric racks and optimized geometry reduce tolerance stacking. A joint with increased internal friction can make steering feel noticeably…well, weird.

Sealed joints with low-friction polymer bearings surfaces offer incredible feel and acceptable life. If you don’t believe me, head down to your local automobile dealership and test drive something with superb handling and a warranty to match. When you’re done, crawl underneath and start counting grease zerks. You won’t find many.

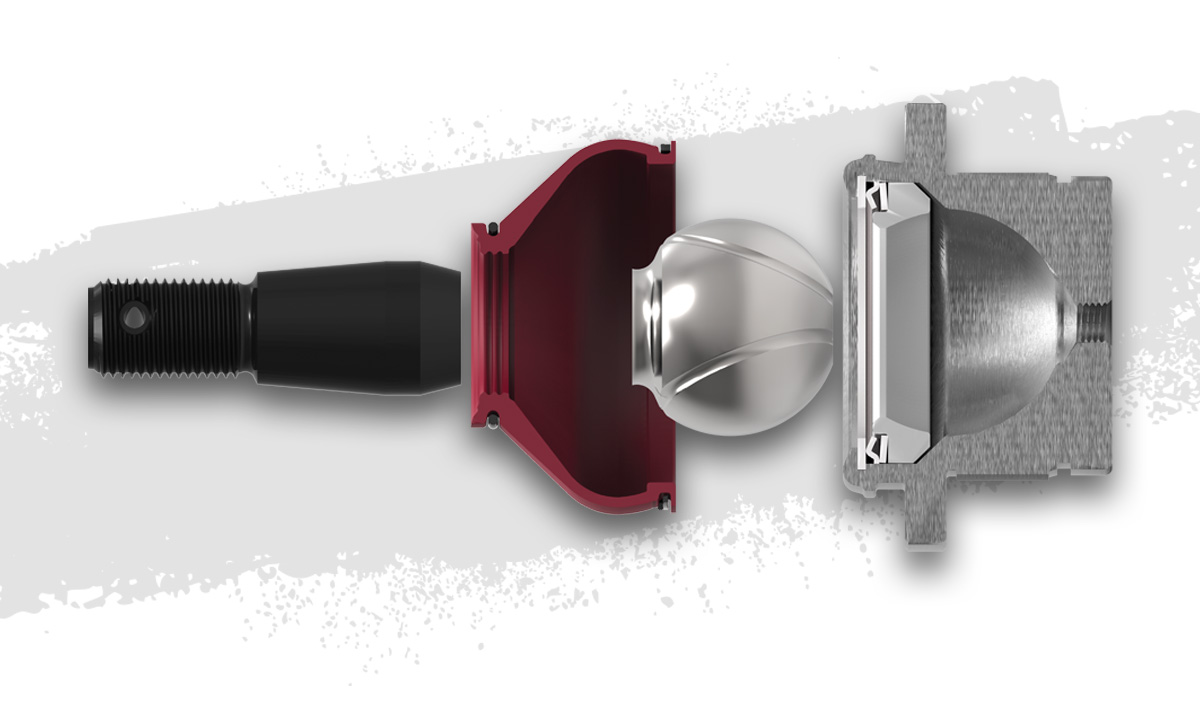

For vehicles that operate under heavier loads and more severe duty, Dorman’s Premium RD ball joints feature a metal-on-metal design with larger bearing surfaces for increased load capacity and a greasable socket to ensure a long service life in all conditions. Photo: Josh Seasholtz.

Those modern chassis designs mean clearance is tight, too. Just because a grease fitting exists doesn’t mean it’s easily accessible after the part is installed. I can’t speak for you, but there are definitely times I’ve fought getting my grease gun nozzle into a dodgy spot or screwed a fitting with an angled into a ball joint or Pitman arm so it can be serviced when in place.

Dave asked me how often I really reach for my grease gun nowadays, and I had to stop and think about that. Increasingly, I’ve seen front-end fittings slowly disappear from passenger cars and some light-duty trucks, and you have too. In fact, it’s happened enough that the ol’ LOF is really more of an oil change nowadays. And that means that in the lube bay, the position in most shops with the highest turnover, fledgling techs aren’t even necessarily looking to lubricate fittings, since seeing them undercar is increasingly rare. It’s almost a self-fulfilling prophecy—even if a customer comes in expecting a lube job, it might not occur.

So do you want a dry metal-on-metal joint in that situation? Or would you be better off with a sealed unit? I know my answer to that question.

Tire maintenance. Photo: Mike Apice.

I’m using some back-of-the-napkin math here drawn from government statistics, but the average number of miles traveled annually in America has climbed from something like 9,900 in 1971 to 13,664 in 2022. An oil change, lube job, and rotation of bias-ply tires used to be the item that would bring a customer to the shop every 3,000 miles, so in 1971 that average driver in the average car would be at the shop three times a year.

But today? Maintenance intervals keep heading north due to better metallurgy, better design, and response to customer preference. Today, tires are often the limiting factor for service intervals—Michelin recommends 6,000-8,000 mile rotations, for instance. Modern oil change intervals are often between 10,000 and 15,000 miles, and if your customers are like mine, many motorists will push the rotations out that long, knowing that doing so won’t sideline the car.

In states with an annual safety inspection, once a year is usually how often a car comes in, often getting its next scheduled maintenance at the same time. Repairs will punctuate this schedule, but that hasn’t changed much over the years.

That means once a year is about when a car is going to get looked over, often by a lube tech or C-level mechanic who is likely rushing and may not take the time to lubricate front end parts—if he even knows to check for serviceable pieces, because those aren’t in play on most vehicles in 2023.

Under those circumstances, Dave told me, sealed chassis parts shine. And you know what? I think he’s right. Fuel injection did a pretty good job supplanting the carburetor. Sealed hub assemblies aren’t repairable, but they require a lot less service than tapered roller bearings ever did. And after thinking about that confluence of factors, a sealed chassis part might be exactly what I install the next time a customer I see too infrequently rolls into the shop.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.