“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

Diagnosing an illuminated check engine light (CEL) is something professional technicians do on an everyday basis. The key to a correct diagnosis is following a logical diagnostic process and gathering the information you need to isolate and repair the cause. The generic OBD-II scan tool provides several resources that will help you gather that information. Before you dive too deep into this post, though, I encourage you to learn more about those resources and OBD-II in general.

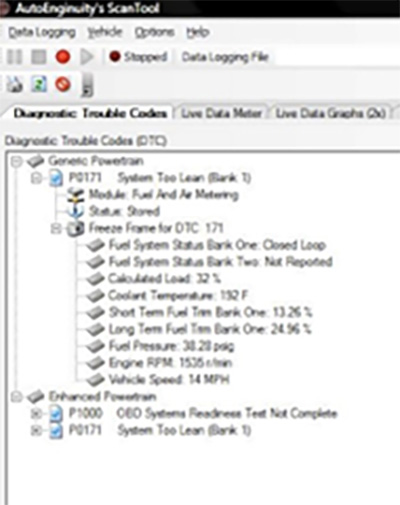

The first step in the process is to use the scan tool to access the diagnostic trouble codes (DTCs) in the engine control module (ECM) that are responsible for illuminating the CEL. Mode $03 is the mode of a generic OBD-II tool used to do this. The $03 is a hexadecimal number that you need not worry yourself about. The hexadecimal is used by the software engineers for programming. Just look for the retrieve code function on the tool’s menu if you do not see it listed by mode.

A common misstep that technicians take after getting the codes is to turn their attention to mode $04. This function clears the codes from the engine control module’s memory and turns the CEL off. It also clears out other information that has not been reviewed yet and is the equivalent of pouring bleach on a crime scene, destroying evidence needed for a successful investigation. Don’t clear anything until you are ready to verify your fix.

Instead, select mode $07. Also known as “pending” codes, these codes are the first failure of a test performed by the ECM. OBD-II codes are generally “two trip” codes, meaning that the failure must occur twice before the ECM is allowed to illuminate the CEL. This prevents the ghost codes for which OBD-I was infamous. Codes in this mode will move over to mode $03 at the second failure, and even if they do not, they can provide additional information that may lead you to the cause of the problem.

Another common misstep is to use only the code description that shows up on the tool’s screen as the basis for a repair. Just because the code has a component name included does not mean that component is the problem. For example, the number one DTC is the U.S. is the P0420 (or its companion, P0430) “Catalytic Converter Efficiency Below Threshold.” This doesn’t mean that the catalytic converter has failed. It only means that it isn’t working as it should.

Instead, take time to do your homework and learn about the code(s) you are attempting to diagnose. The more you know about them, the better. There are numerous sources for information, but before you rely on the results of a generic internet search, be sure to vet the source! And always test your guess before you replace a part that may not need replacing.

The article I referenced at the beginning has a number of popular sources for valuable information. Rely on those first before trusting information sources that may or may not be reliable.

When researching the code, the more you know, the better. How did the ECM assess the component or circuit? You may be able to mimic those tests to help you in your troubleshooting. What did the ECM see or not see that caused it to record a trouble code? The ECM is going to check your work, and if the repair you make does not satisfy its test requirements, the CEL will just illuminate again. What are the conditions that must be present for any of the tests to be performed? Some components are evaluated continuously for problems, while others are only checked once during any given operational cycle of the vehicle. In some cases, the vehicle may have to sit overnight in preparation for a test or be driven in a certain manner for the test to be conducted.

Often overlooked are what components or systems will not be evaluated if the DTCs recorded are active. This scenario often sets the stage for a future problem. Once the first codes are repaired and then cleared, the ECM will be able to move on to assessing these overlooked systems and may discover issues in them that cause the CEL to illuminate once more. For example, the ECM has recorded a misfire code for one of the engine’s cylinders. If this code remains in the ECM’s active memory, it will not evaluate systems like the catalytic converter until that is corrected. Yet, the misfire could have damaged the converter by causing it to overheat and its substrate to begin to melt. Once the misfire issue has been corrected and the ECM’s memory cleared, the converter failure will be identified, and there will be a new DTC to diagnose. And potentially an expensive additional repair to be made.

I alluded earlier to tests that were performed repeatedly versus ones that are only performed once. Let me explain that a bit more.

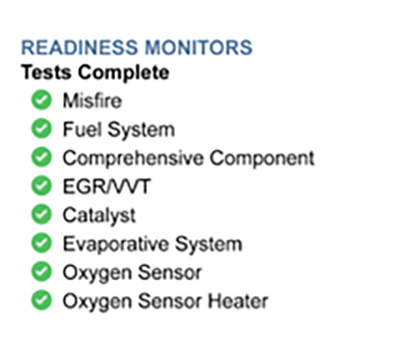

The ECM can assess everything attached to it. These tests are grouped into sections relative to the systems or components being assessed. These are the monitors you will see when using mode $01 or using the tool’s access readiness monitor status command.

Only three of the monitors are composed of tests that are repeated during any given drive cycle, or operation cycle, of the vehicle. They are the misfire monitor, the fuel monitor, and the comprehensive component monitor. All three are vital to maintaining the condition of the catalytic converter, and that impacts emissions.

All the others are noncontinuous and only run once during a drive cycle. Common monitors include the oxygen sensor heater monitor, the oxygen sensor monitor, the evaporative emissions system monitor, and the catalytic converter monitor. While some are common to all makes and models, there may be noncontinuous monitors that are unique to a particular brand.

When you are looking at the status of these monitors, you may see them listed as “ready” or “not ready.” You may also see “complete” or “incomplete.” On any vehicle, if you see a “not available,” it means that that monitor does not apply to that vehicle.

The very first time the ECM completes all its testing, it will flag the monitors as completed. And here is an important fact: they will stay that way unless one of two things happens. First, the battery is disconnected, and second, the codes are cleared using a scan tool. If you see any that are not completed, you know that someone has been there before you and attempted a repair that did not work. You should also be on guard for any monitor that has not yet been completed, because it is waiting for the current fault to be fixed.

Another important fact to remember is that just because a monitor says complete, it does not mean there were no faults found. It only means that all the conditions needed for the ECM to perform the tests that make up that monitor have been met and all the tests have been completed. Rerunning the monitors after the repair has been made and then checking in mode $07 for the return of the code you corrected is a good way to verify that your repair is pleasing to the ECM.

Mode $02 on the generic OBD-II scan tool is known as freeze frame. This is a vital piece of information to review right after you have checked modes $03 and $07, especially when the code involved is a result of a continuous monitor. Since these codes are evaluated all the time, over and over, it means they are also being evaluated under a variety of engine load and rpm conditions. This helps you understand how the vehicle may have been operating under when the problem occurred. If you have a misfire issue, for example, that happened at freeway speeds while passing a truck, trying to find that same misfire while the car is idling in your work stall may be impossible. Make a note of this information before you use mode $04, or you will wipe it all away.

Any good diagnostic process starts by verifying the concern, checking for DTCs, gathering information, and then forming a hypothesis of what the causes may be. Then we test the system or components to either confirm or disprove that hypothesis, using the information gained to develop our next one.

An important initial step is to use a qualified service information system to check for technical service bulletins (TSBs) early on. Since these are computer-controlled systems, many faults are corrected by updating the software. If that is the case with your car, a trained professional should be consulted to conduct the reprogramming.

A common mistake is to jump to conclusions early on and replace parts before confirming that they are the cause of the fault code. Always assess your hypothesis before making the repair.

Another common mistake is to perform detailed tests of individual components before testing the systems at large. The idea behind testing is to eliminate as many potential causes as possible at one time until you only have a few suspects left. Then you can do more specific tests. Beforehand, though, remember that there are only four things that can make an engine run badly.

They are:

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.