“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

We’ve all read articles on brake jobs and are familiar with the standard tips. Check the rotor thickness and runout. Pay attention to pad wear patterns. Don’t add fluid to the system when pads are worn. Blah, blah, blah. Here’s another list of tips that’s slightly less orthodox, but still might help you out.

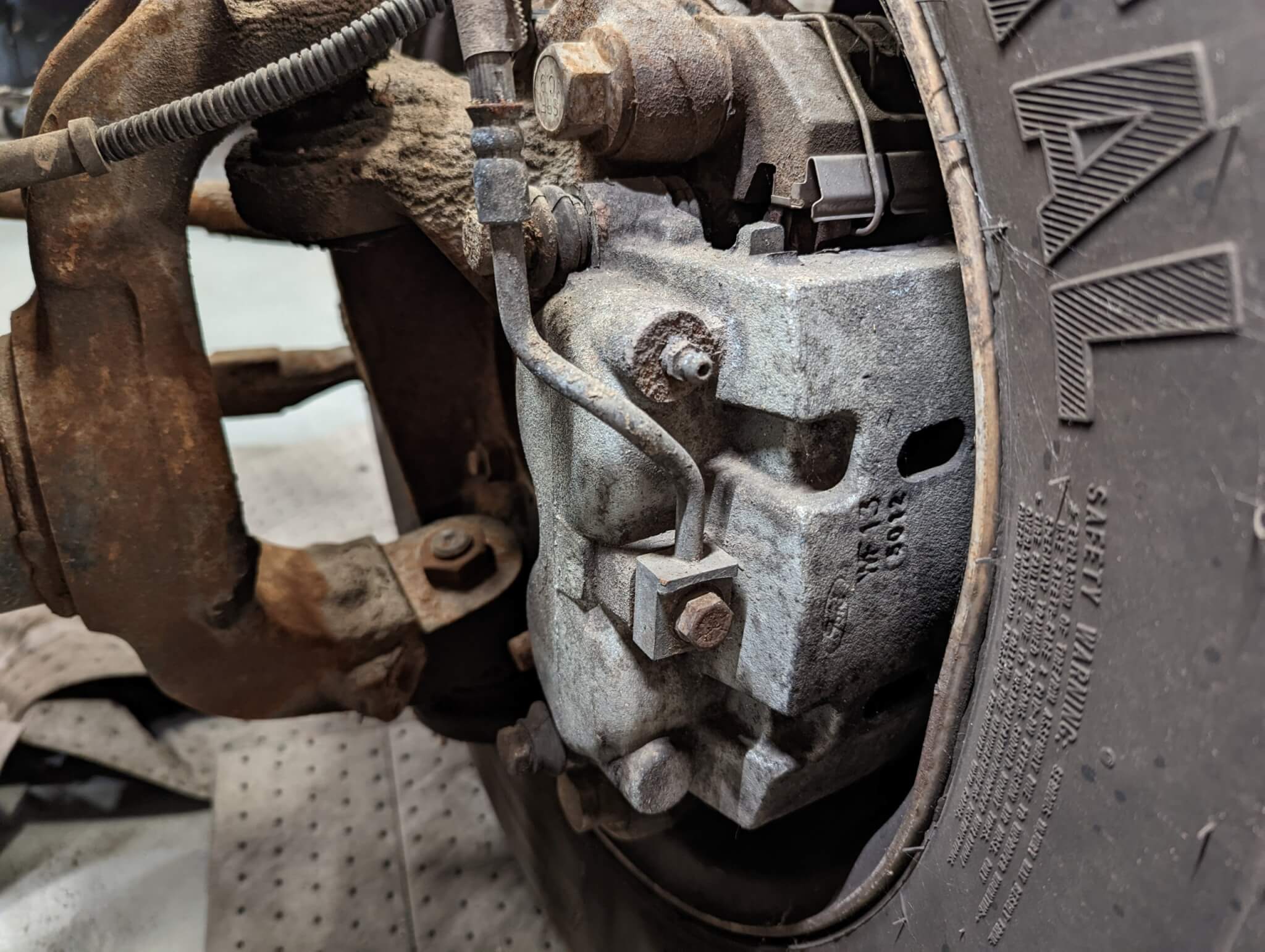

Will a pad slap suffice here, or is deeper repair required? Each vehicle is different, so why not treat them that way? Photo by Lemmy.

In the shop? It’s fine to say it. But I’ve excised this term from my lexicon with my customers. I’m pretty sick of getting beat up over the price of my brake job. “Well Joe over at Joe Blow’s House of Automotive Values can do my brake job for a third of what you’re charging.”

Sure. That’s because Joe is going to slam in new economy pads and ship the car. Joe hasn’t seen your torn caliper pin boots. Joe just has a menu price that he’ll jack up if something is really amiss, and everything else just gets sent out the door if it’s not dangerous. But as we all know, there is a big chasm between “not dangerous” and “complete and ready to rock.” (More on that in just a minute.)

If I’m servicing front brakes, I’m assuming you’re getting new pads, new rotors, new shim clips, and pin boots. There’s a good chance new slide pins will be needed. When I’m done, I’m also going to spend some time on your other axle. (More on that, too.)

Joe’s job might work OK… but it could also turn out to be a little noisy. Joe’s job could have a little pulsation in the brakes that may or may not cause a customer return. If a customer is sensitive to price, I’m happy to start paring down my cost, but I do like to let the customer know why that delta in price exists in the first place. The problem, I think, lies with the name of the service. We both call this a “brake job,” which sounds like it is in fact a complete job. But like “remanufactured” and “rebuilt,” there are varying levels of completeness and quality which must obviously carry different prices.

Obviously, I expect as a professional you’re using lube when you do a brake job, at least on the guide pins and probably on the backs of the pads. But I’ve found that spending some time with the wire brush and the cup wheel on caliper brackets pays off in spades. Yes, the job takes longer, but by cleaning up the pitting where the pads (or shim clips) ride in the brackets, the potential for noise plummets.

I also see much more even pad wear. Here in the Northeast, I regularly have to beat pads out of the brackets. If they ain’t free to move, there is no way they’re going to wear evenly, and braking performance will suffer. In extreme cases, they’ll mimic a hydraulic problem where one may not exist.

Brake lubricant is cheap—another dime’s worth of grease in the right places is one of the biggest bang-for-the-buck processes I’ve implemented in the shop.

Traditional brake cleaners can be expensive, are usually pressurized and when used may send carcinogenic powdered friction material airborne after you point and shoot. Simple Green and a scrub brush work fine, and so does soap and water. They take longer, but if you stick with that stuff, you’ll last longer.

Effective, but at what cost? Photo by Lemmy.

Many years ago, I remember the ASE changing their recommendation for cleaning brakes to soap and water and I thought they were a bunch of nerd-os. But they’re right, soap and water clean well even though it requires more effort. And according to the doc, it doesn’t damage my liver like brake cleaner has.

In my shop, drum brake overhauls get a flat two-hour labor rate. They just take longer to do—there are more parts to clean and inspect, and they take longer to reassemble, so I charge more. I make no apology for that, but some shops have menu pricing that is the same between disc and drum, and I think that’s silly.

Servicing drum brakes encompasses more than replacing shoes and drums. Photo by Lemmy.

Remember when I said I work on the other axle when I’m done with front brakes? Part of my brake job price on the front includes a cleaning and adjustment of rear brakes. (I recommend these independently, too, when a car just has poor pedal feel when I’m test driving.) Nothing drives home the point of a complete brake service like a nice, responsive pedal that rides higher when drivers throw the anchors out.

Mechanics are often accused of replacing things that don’t need replacing, but in my shop, it’s been the exact opposite—I get asked to replace things that are fine. Cars come in for noisy brakes and often I service them (cleaning and lubricating), but leave the consumables (like friction products) in play. “Why don’t you just replace the pads and rotors while you’re in there?”

Well, because the parts you have are still serviceable and the bill is going to skyrocket, right?

“Your pads are 30% worn” to you and I mean that there is lots of life in a set of brakes. But customers? Customers hear that as “Your brakes are only 70% effective.”

I used to fight with these people to help them keep their bills low, and then a customer gave me some advice that I have followed ever since. He basically recommended I do the job because he could afford it and he’d feel more confident in his car. “It’s not that I don’t trust you, it’s just that my brain will stop worrying about it and for the extra few bucks, I can just move on with my day.”

Now I make sure to talk with customers about what brake work I recommend, and I let them make the call. They’re the ones driving their cars, and they need to feel safe doing it.

So keep doing all the conventional best practice items in your brake jobs, but maybe try out a few of these less-than-obvious tips and see if they don’t augment your already-solid work in the shop.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.