“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

Pop quiz, no cheating: how many amps does the ground side of any circuit conduct?

If you said, “As many as the hot side,” get yourself a gold star and skip this article. For the rest of us who weren’t born innately knowing the answer to that question, stick with me for a moment here while I point out a few things about modern vehicles.

If you fix jalopies for a living, you can see where I’m going with this. I am guilty of having assumed a good ground in a circuit, and I bet you are too. Oh, I might have whipped out my meter and spun the dial to the audible continuity tone and verified I got a little beepy-doo, and I might even have tested the resistance. But one little strand of copper hanging in there sometimes passed those tests with flying colors and yet left circuits unable to function reliably.

As a young mechanic, I was taught to inspect and clean all grounds when I had an electrical problem on my hands, and I think that’s good advice. But it ain’t great advice: Nowadays, I hatehatehate changing things in any system without measuring and testing them before and after a change.

I test my grounds before I clean or tighten a dang thing and I suggest you do, too. That way, if that was the problem, you can say so empirically.

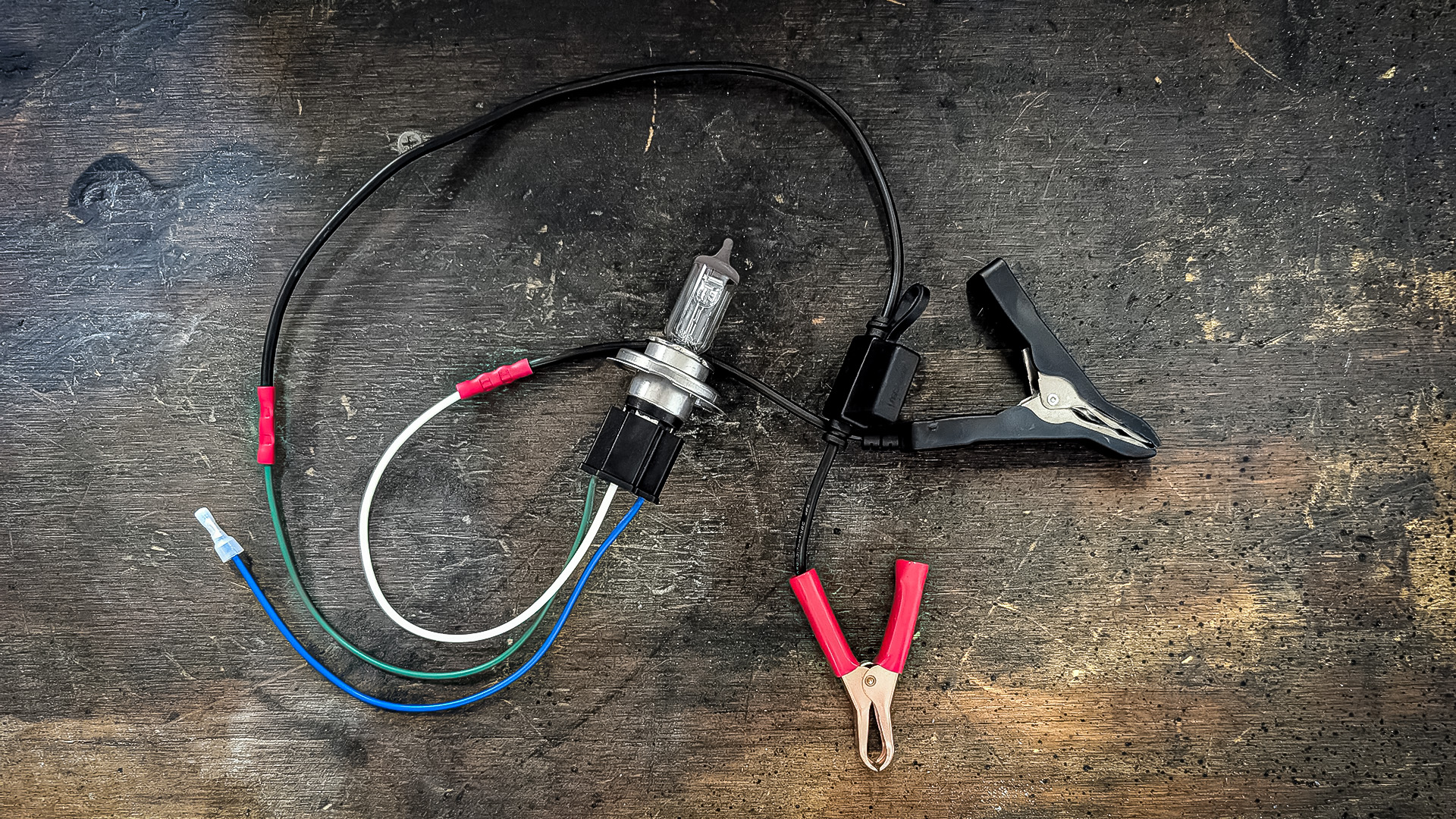

Nothing fancy here that can’t be plucked from the donor car out back. Photo: Lemmy.

Here you can see a test rig I’ve stuck together from new parts; I really splashed out. You can, of course, duplicate this thing from scrap parts for peanuts. This is a test light in a sense, but you’ll notice this one is a halogen, and that’s because this is in effect a cheap load tester. You know why we use battery load testers; meters don’t tell the whole story. Circuits are no different.

I got this bulb wired up to the high beam filament in an H4/9003 headlight bulb. Let’s do some back-of-the-napkin math: Nominally, that’s a 60 watt load running on roughly a 12 volt system, and while we can’t directly convert that, we can rough that out to about five amps. (What’s an amp or two between friends?) The 16 and 18 gauge wires that snake around most vehicles should easily handle a five amp load at the lengths found in most auto wiring harnesses.

So now we have a way to stress-test a ground circuit before cleaning or tightening a single thing. Clip the hot side on the battery, and then grab your test lead and test the exact ground path your malfunctioning component is using. Light wonky or not working at all? Bingo, you’re on the case. And if not, no biggie, but at least now 50% of the circuit has been ruled out definitively.

A thing I like about good ol’ fashioned burnin’ filaments is that they respond visually to changes in the circuit, so this is also a half-decent fault-finder, too. You could unhook the tester that isn’t lighting up and start disassembling the ground side of the circuit—but you could also have the lube rack kid hold the bulb and both of you could observe it flickering as you start feeling and moving things, helping you isolate the area of the mechanical fault causing the electrical problem. (You should do that, too. Everyone’s mean to the lube rack kid, but he needs some of the smarts between your ears to feed his family, too.)

If you haven’t been load-testing the other half of the circuit, now you can quickly and easily. While you’re paying attention to the poor neglected minus sign, I might also encourage you to check out this oldie but goodie from colleague Pete with some more intel on why the “meter on the chassis bolt” isn’t a definitive test.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.