“Drive it ‘til the wheels fall off” isn’t the safest decision. So when does it end?

It’s possible you have already heard of Preston Tucker. He was the subject of “Tucker: The Man and His Dream,” a 1988 Francis Ford Coppola movie starring Jeff Bridges. More recently, he was the subject of the biographical book “Preston Tucker and His Battle to Build the Car of Tomorrow” by Steve Lehto (with a forward by Jay Leno) that was published in 2016. If you know anything about him, it’s likely the fact that he planned to manufacture a line of cars called the Tucker 48, that featured many engineering and safety features that were later adopted by other car manufacturers. However, he was also accused of fraud and was the target of an SEC trial that bankrupted his company and led to only 50 complete Tucker 48s being produced. So was Tucker a visionary or a villain?

Photo: The Tucker Historical Collection and Library, via Wikimedia Commons. Retouched by W. Guy Finley.

Preston Tucker was born near Capac, Michigan, on September 21, 1903. From an early age, Tucker was obsessed with cars, first learning to drive at age 11. At 16, he started buying old cars, repairing and refurbishing them to resell. He dropped out of high school and started working as an office worker for the Cadillac Motor Company. In his young adult life, he joined the Lincoln Park Police Department (mainly because he wanted to drive the fast, high-performance police cars and ride motorcycles), worked on the Ford Motor Company assembly line, and ran a gas station with his wife. While managing the gas station, he began selling Studebaker cars on the side. This led to later successive jobs selling Stutz, Chrysler, Pierce-Arrow, and Dodge cars.

From 1932 to 1943, Tucker started a succession of companies to manufacture race cars, armored combat vehicles, and aircraft and marine engines. Comparatively, the most successful of these projects was the armored combat vehicle. In 1939, with war looming in Europe, Tucker came up with the concept of developing a swift fighting vehicle. To this end, he designed the Tucker Combat Car (a.k.a. the “Tucker Tiger”) featuring the Tucker Gun Turret (a fast-moving electrically powered gun turret). The Netherlands showed interest in the idea, as they sought a combat vehicle appropriate for the muddy Dutch landscape.

Photo: Tucker Combat Car. Public domain.

Before Tucker could close the deal, however, the Germans invaded the Netherlands in the spring of 1940. He then tried to sell the vehicle to the United States military, but they considered it too fast. In the end, only one prototype of the combat car was built, although it is said to have reached 100 mph, far exceeding Tucker’s predictions.

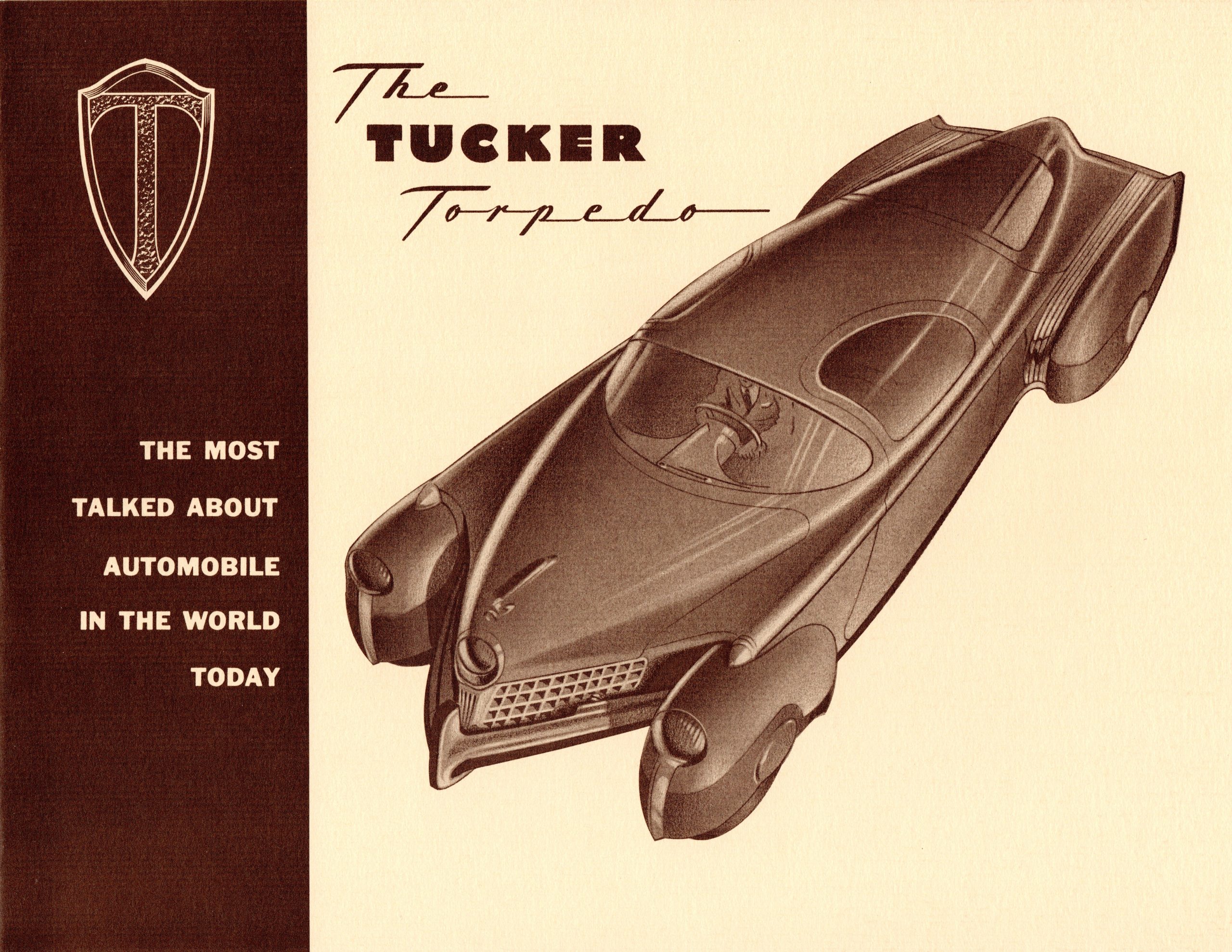

The saga of the Tucker Corporation and the Tucker 48 began in 1944. The public was ready for new automobile designs after the war, but the Big Three auto manufacturers had not created any new models since 1941 and were not in a rush to do so. Recognizing this, Tucker designed a safe car with innovative features and modern styling, featuring a liquid-cooled flat-6 engine with aluminum block, four-wheel independent suspension, seat belts, a padded dashboard, and instruments all located within the driver’s field of view. Initially called the Tucker Torpedo, Tucker eventually renamed the car to the Tucker 48 to avoid negative connotations with World War II, which had recently drawn to a close.

Only six bolts held a separate subframe (on which the engine and transmission were mounted) to the body. This meant that the entire drivetrain could be lowered and removed from the car in 30 minutes by one man. In fact, it only took 18 minutes for three mechanics at the factory to accomplish a complete engine swap. In order to illuminate the route around corners, Tucker installed a third directional headlight in the front center of the vehicle. This bulb would turn on when the vehicle wheels were aimed 10 degrees beyond the centerline of the vehicle, with the adaptive light following the steering wheels in the direction they were pointed. A rear engine, rear wheel drive configuration and headlamps that turned with the front wheels had been available in other cars, but they would have been firsts for an American production car. The car had a roll bar built into the top and a perimeter frame for crash protection. To safeguard the driver in a front-end collision, the steering box was placed behind the front axle (this predates the introduction of the collapsible column but solved the same problem). The dashboard was cushioned for safety, and the windshield was constructed of impact-resistant glass intended to pop out instead of shattering in order to protect the passengers. The parking brake featured a separate key that could be used to lock it in place to deter theft. To make entering and exiting easier, the doors extended into the roof, creating a larger opening to reduce head bumps against the door frame. Some of the innovations that Tucker envisioned were later abandoned due to changes in design, cost, engineering complexity, and lack of time to develop: magnesium wheels, the centrally located steering wheel, disc brakes, fuel injection, self-sealing tubeless tires, and a direct-drive torque converter transmission. However, many of these were later seen on other vehicles.

Photo: Tucker Torpedo brochure, c. 1947. Note the marked difference of the look of the vehicle in this brochure versus the photos of the manufactured cars below. Source: Alden Jewell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

One of Tucker’s problems with media and public perception started early, stemming from the fact that there was a rotating cast of designers that worked on the car. From 1944 to 1946, noted car designer George S. Lawson worked on the 48’s design. Then, designer Alex Tremulis worked on the car for three months. He was followed by five designers from the New York design firm J. Gordon Lippincott. However, Tucker also hired back Tremulis during this time, having him and the Lippincott team develop competing clay models for Tucker to choose from, with Tucker choosing the Lippincott team’s design. The Tucker 48’s disparate look in the company’s press releases and other promotional materials, along with oblique claims like “15 years of testing produced the car of the year,” despite there being no operational prototype at the time, all contributed to the government’s and the media’s growing suspicions that something was fishy about Tucker’s vehicle.

If the seeds of doubt were planted by the changing design of Tucker’s car, the Tucker 48’s premiere dumped a ton of water on those seeds to help them grow. Over 3,000 people showed up for the world premiere of the Tucker 48 prototype (nicknamed the “Tin Goose”) on June 19, 1947, at the Tucker factory in Chicago. Prior to the premiere, two of the prototype’s independent suspension arms snapped under the car’s weight, the experimental 589-cubic-inch engine was extremely loud, and the high-voltage starter required the use of outside power to get the engine started. The liquid coolant overheated as the automobile was being driven onto the platform at the premiere, allowing some steam to escape from the vehicle. Finally, the prototype could not go in reverse because Tucker had not had time to finish the direct torque drive before the car’s premiere.

Newspaper columnist Drew Pearson reported that the car was a fraud because it could not go backward and it made a “goose-geese” sound going down the road. Pearson’s comments were indicative of the large amount of negative press that Tucker’s car received following the premiere. Over the next two years, a total of 51 Tucker 48s were completely or partially built, addressing the issues that were present at the premiere.

Photo: Tucker 48, chassis number 1044, owned by Howard Kroplick. Photo by Rob Ida.

Photo: 1948 Tucker. National Motor Museum/Heritage, Images/Getty Images

For his manufacturing location, Tucker chose the old Dodge B-29 assembly plant in Chicago, Illinois, which was then the biggest single-building factory in the world. With the condition that Tucker raise $15 million in working capital by the following year, the War Assets Administration (WAA) leased the facility to Tucker. Because collaborating with wealthy businessmen would have required giving up control, Tucker chose a more creative method of raising money: he sold dealership rights to businesses eager to market the Tucker 48 to a waiting public. To raise even more money, he offered shares of Tucker Corporation stock to potential customers and even allowed customers to ensure their place on the Tucker dealer’s waiting list by purchasing accessories for their cars in advance.

That last idea may have been a step too far for the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, and Tucker was investigated by the SEC and the United States Attorney. Tucker turned over his corporation’s records to the SEC in 1949. In February 1949, a grand jury inquiry was started by United States Attorney Otto Kerner Jr. Tucker and six more officials of the Tucker Corporation were charged with 25 counts of mail fraud, five counts of violations of SEC regulations, and one count of conspiracy to defraud on June 10. The trial began on October 4, 1949, and the Tucker Corporation’s factory was closed on the very same day. The government argued during the trial that Tucker had no intention of building an automobile.

According to Steve Lehto’s book, the SEC report on Tucker was kept secret throughout the trial and Tucker’s counsel were never permitted to see or read it, but it was nonetheless leaked to the media. In fact, Collier’s published a piece criticizing Tucker that contained leaked information about the SEC findings. Additionally, Reader’s Digest reprinted this article, leading to even more bad press for Tucker. Finally, on January 22, 1950, after 28 hours of deliberation, the jury found all defendants to be “not guilty” on all charges. Although Tucker had won the trial, the Tucker Corporation, which had lost its factory, was now heavily in debt, facing numerous lawsuits from irate Tucker dealers, and essentially bankrupt.

In the early 1950s, Tucker looked to return to the auto industry by developing the Carioca sports automobile with help from Brazilian financiers and auto designer Alexis de Sakhnoffsky, according to Ken Gross’ April 2012 article, “Tuckers Soaring 64 Years After Splattering” in Sports Car Market magazine. However, Tucker’s travels to Brazil were plagued by fatigue, and Tucker died from pneumonia as a complication of lung cancer on December 26, 1956.

Regardless of the outcome of the trial, rumors have persisted on the issue of whether Tucker actually planned to build a new automobile and market it, or whether the whole operation was bogus, created with the express intention of obtaining money from unsuspecting investors. So, was Preston Tucker a visionary or a villain? Ultimately, I believe Preston Tucker was a great salesman who may not have been quite as skilled at running an entire business; an “idea man” who didn’t take adequate time to consider the logistics. Between the confusion over the car’s design due to multiple designers working on the car at different times, many features that were promised early for the car that never materialized, the troubled premiere of the car, and Tucker’s innovative/suspicious approaches to raising capital, it’s easy to see why his venture was viewed with skepticism.

In addition, Tucker’s timing was not great. The SEC at the time was on alert after small automaker Kaiser-Frazer had recently received millions of dollars in grants for the development of a new car but wasted the money. While Tucker did not accept any funding from the government, small, up-and-coming automakers were subject to intense SEC scrutiny at the time. Furthermore, Tucker believed that the Big Three auto manufacturers were impeding his attempts to produce his cars, as he subtly hinted at in “An Open Letter from Preston Tucker” that was published in many newspapers on June 15, 1948. I won’t go so far as to say that a Big Three conspiracy was at work to stop Preston Tucker, but it’s certainly not implausible that the Big Three were applying political pressure to put an end to his production.

Finally, of the 51 Tucker 48s that were completely or partially built, 47 are still in existence, with photos and the location of each car tracked on the Tucker Gallery at the Tucker Automobile Club of America’s website. Other car manufacturers later adopted many of the engineering and safety features introduced on the Tucker 48. In addition, as of October 31, 1948, the company had $16 million in assets and only $2 million in liabilities. I believe that the longevity of the existing Tucker 48s, the influence they had on other car makers, and the financial solvency of the Tucker Corporation proves that Tucker was a visionary, fully intended to build these innovative cars, and had the means to do so.

The articles and other content contained on this site may contain links to third party websites. By clicking them, you consent to Dorman’s Website Use Agreement.

Participation in this forum is subject to Dorman’s Website Terms & Conditions. Please read our Comment Policy before commenting.